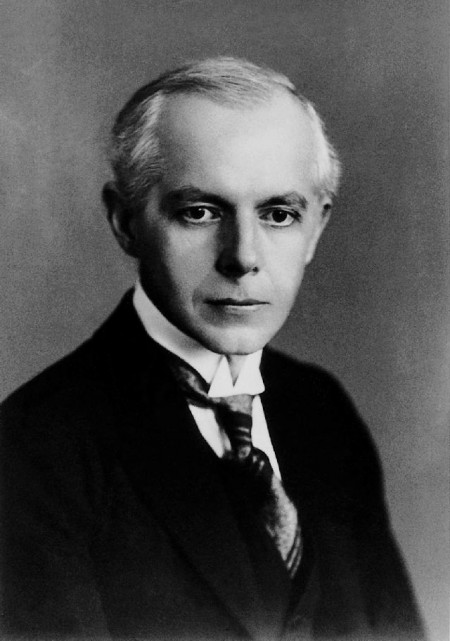

25 March 1881, Nagyszentmiklós – 26 September 1945, New York

Béla Bartók was one of the classic composers of the 20th century, the greatest Hungarian composer besides Liszt. As an ethnomusicologist, he, together with Kodály, laid the foundations for the collection of Hungarian folk music; with the Romanian and Slovak collections, Bartók placed the national task at an early stage into the context of comparative music folklore.

Bartók was born in 1881 at Nagyszentmiklós (today Sinnicolau Mare, in Romania). His teacher mother was his first piano teacher. He lost his father, who was the headmaster of an agricultural school, when he was seven. He matriculated in Pozsony (today Bratislava), where he also received a more through musical education. On Dohnányi's advice Bartók chose the Budapest Music Academy, instead of going to Vienna, for the next stage of his studies. Between 1899 and 1903 he completed the course in piano as István Thomán's pupil, and also the course in composition, studying with Hans Koessler.

After the childhood dance pieces and the increasingly higher standard romantic cycles, it was not his studies at the Academy but the experience of hearing Richard Strauss' Zarathustra that led to his early large-scale works. The Kossuth Symphony, which had a highly successful premier in Hungary in 1904, was a naive attempt to create a national art-music. In 1905 he had a setback at the Paris Rubenstein composition and piano competition. From that year onwards he began his regular collection of folk music, in which Kodály's advice was of great help to him. The jointly published Hungarian folk songs (Magyar Népdalok, 1906), containing twenty settings, signals their concept: they wanted to base the new musical style and education, instead of the volkish art-songs, on the melodies collected from the peasants. This idea remained constant in Bartók's pedagogical works, from the For children (Gyermekeknek, 1908-09) to the Forty-four duets (Negyvennégy duó, 1931), written for violins; while the Mikrokosmos (1926, 1932-39) is connected to the programme more indirectly.

His Op. 1 Rhapsody (1904) and First Orchestral Suite (1905) still accorded with the expectations of an audience brought up on Liszt, Brahms and volkish art-songs. Becoming – at Kodály's recommendation - acquainted with the music of Debussy, following that of Strauss and Reger, as well as a personal crisis (his unrequited love for the violinist Stefi Geyer), helped him to significantly renew his style with harmonic, rhythmic and other compositional experiments, building the elements of folk music in a multifaceted way into his musical language (Fourteen bagatelles, 1908). Later on Stravinsky and Schönberg also exercised a decisive influence on his stylistic development, which always reacted sensitively to the spirit of the age.

He joined the teaching staff of the Music Academy in 1907 as the successor to his own piano teacher, István Thomán (Translator's note: Liszt's onetime pupil). Though he requested from the early years that he be employed as a collector and organiser of folk music, his permanent occupation remained teaching the piano till 1934, when he was moved to the Academy of Science. He married his first wife, Márta Ziegler, a private pupil of his, in 1909. In 1911 – the year of the emblematic Allegro barbaro – his only opera, Bluebeard's Castle, composed on the basis of a mystery play by Béla Balázs, was rejected at the competition held by the Lipótvárosi Kaszinó. The New Hungarian Musical Society, organised with his participation, was unable to survive. The following period of seclusion was also the time for his Arabian collecting trip and of a new stylistic period, beginning with the Piano Suite. The 1917 premier of his ballet, The Wooden Prince, not only won over a new audience, but also gained him a contract with the Universal Edition of Vienna. A year later his opera was also performed, with success.

From 1920 onwards, Bartók gradually became involved in the re-awakening musical life of post-war Europe. Following his initial concerts in Berlin, London and Paris, he went on regular concert tours all over Europe, writing folk inspired expressionist violin sonatas for his appearances with Jelly Arányi. In 1928 he toured the United States, in 1929 the Soviet Union. He married his Music Academy pupil, Ditta Pásztory, in 1923. The Dance Suite, which he composed for the fiftieth anniversary of the unification of Buda and Pest, only achieved a great success in 1925, in Prague. His pantomime, The Miraculous Mandarin (1918-24), was banned after its premier in Cologne because of Menyhért Lengyel's text, on which it was based. Instead of stage works, Bartók turned to oratorios. In the Cantata Profana (1930) he set to music a Romanian folk ballad's (kolinda) text, which he had himself collected. In his piano works composed from the middle of the twenties (Sonata, Szabadban, First Piano Concerto), neo-baroque elements made an appearance, after which he developed his symmetric great forms (Fourth quartet, Second Piano Concerto, Fifth Quartet). In the second half of the thirties the compositions (Music for strings, percussion and celesta, Sonata for two pianos and percussion, Divertimento) commissioned by Paul Sacher were performed all over the world. The Violin Concerto marks the beginning of his late period. The six string quartets (1908-39), which accompanied his various creative periods, play an important role in establishing the classic rank of his life's work.

At the beginning of the Second World War, instead of the Universal Edition, which had fallen into National Socialist hands, he entrusted the publication of his works to the London Boosey and Hawkes company, and sent his manuscripts abroad. In 1940 he left for the United States. The Concerto, composed for orchestra, commissioned by Serge Koussevitsky, was written in 1943, after a longer period of silence and a lengthy illness. At Yehudi Menuhin's request he composed a violin solo sonata (1944). He left behind the almost completed score of the Third Piano Concerto, intended for his wife, and the outline of the Viola concerto, when he died on 26 September 1945 in New York.

L. V.