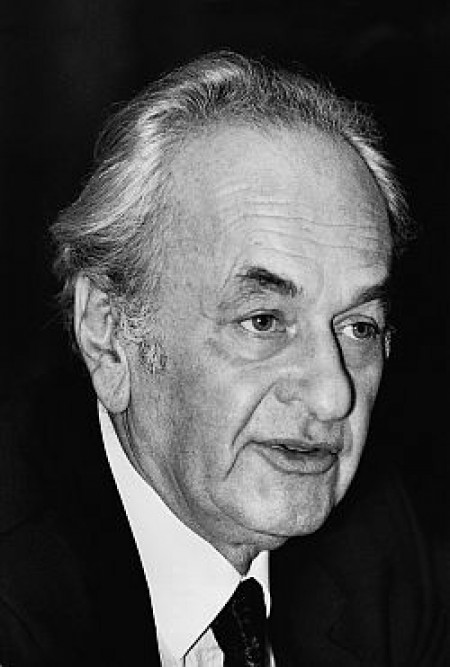

28 December 1928, Budapest – 30 November 2016, Budapest

Musical talent is often inherited through direct descent, but only rarely in a "knight's progress". Kamilló Lendvay's case is among those exceptions which strengthen the rule. His uncle, Ervin Lendvai, graduated with Kodály at the beginning of the century, and then worked in Germany as a prestigious composer, professor and choir conductor. He died in London in 1949, the year in which János Viski admitted his nephew to the composition class of the Music Academy.

Kamilló Lendvay completed various academies. Before entering Viski's classroom, he had played the piano in the jazz symphony orchestra of the Angol (now Vidám) Park. (Translator's note: permanent fairground in Budapest). And hardly had he entered the class, he had to – temporarily – leave it again. Due to an administrative error, he was called up for military service, even though university and college students were exempt. No authority was willing to correct the mistake. So Private Lendvay served his time, learned to play the trumpet and formed a wind ensemble. It is hardly surprising that it was not until 1957 that he completed his studies, during which time he also attended László Somogyi's legendary conducting classes.

Preparing for a career as a musician, he attended the practical schools of the mass genres, and, as some kind of post-gradual self-training, undertook various tasks in musical praxis for over a decade and a half. These included working as conductor at the Szeged National Theatre, musical director of the State Puppet Theatre, artistic director of the Army Ensemble, conductor and then musical director at the Budapest Operetta Theatre, and, from 1962 onwards, musical lector at Hungarian Radio. After these diverse musical activities he became a teacher of theoretical subjects at the College of Music in 1973, and then head of the music theory department between 1977 and 1995, first with the rank of Reader, and then as Professor.

It is no accident that I lingered for so long at Kamilló Lendvay's "academies". This vast practical experience has had a significant impact on his work as a composer. Lendvay thinks in terms of specific performers even when sitting in front of a sheet of music. To stay with the not too distant past: he wrote his Second Violin Concerto (1986) with Vilmos Szabadi's technique and personality in mind, his Trumpet Concerto (1990) for György Geiger, his Saxophone Concert (1996) for László Dés. And before we regard the years spent in the army as wasted time, let us recall that the military brass band served as a kind of preliminary study for the wind ensemble setting of his early, internationally highly successful, Piano Concerto (1959) and Trumpet Concerto. What he learned in the theatre, he utilised in musical plays, musicals, ballet music (Pécs), and finally in operas; in the Magic Chair, written on the basis of a Frigyes Karinthy (translator's note: great Hungarian writer in the first half of the 20th century) work, which in 1972 was the opening production of the Musical TV Theatre, and in writing music for the Sartre drama, The Respectful Prostitute (1979, Hungarian Television, performed on the Paris stage, where the recording made of it won a first prize).

He started from Bartók, as did so many of his contemporaries, but then soon enriched his musical armoury with new impulses. He enriched it, but the acquisition of the new elements of technique did not interfere with his own musical sound, his personal property. His First and Second Violin Concertos are separated from each other by a quarter of a century – a vast expanse of time in our ever more rapidly changing world – but they are connected by the composer's characteristic melos, his exactingness regarding form, and variety of expression.

I cannot provide here a full list of compositions covering his rich life's work, and even less detailed analyses. Perhaps I can be sufficiently subjective and unjust though to emphasize, besides the pieces mentioned already, the lived emotional storm of his Pezzo Concertato for Cello and Orchestra, written in 1975, which won a competition in Trieste, the heart sounds of the 1981 Jelenetek (Scenes), inspired by Thomas Mann's work, and the burning drama of Via crucis (1989).

J. B.