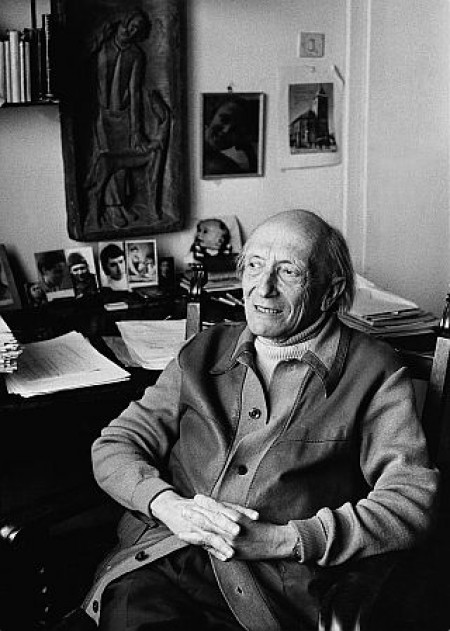

24 April 1897, Budapest – 16 August 1984, Budapest

György Kósa entered the Music Academy in 1908, on the recommendation of Béla Bartók. On the practical teaching course he was taught by Sándor Reschofsky, in the preparatory class by Arnold Székely (1909-12). He became officially Bartók's pupil from the 1912/13 academic year, and received his artist's diploma as pianist in 1916. On Bartók's advice he repeated the fourth year academic class, which is how he became Ernő Dohnányi's pupil, who in the meantime had returned to Hungary. Besides studying the piano, Kósa also developed an interest in composition. He attended first Zoltán Kodály's composition classes (1910-11), and then (1911-1915) Viktor Herzfeld's.

From the beginning of the twenties, Kósa became the accompanist of several important Hungarian and foreign soloists, among them Mária Basilides, George Enescu, Bronislaw Huberman, Henri Marteau, Vilma Medgyaszay, Jenő Hubay and József Szigeti. He played a significant role in popularising Bach's music in Hungary, as well as in advancing the cause of contemporary music. From the 1927/28 academic year he became a fee-earning teacher at the Music Academy. As a composer, he had international successes with his Six orchestral pieces (1919). In the twenties and thirties more and more of his works could be heard at concerts: his Two orchestral Ady songs (1924), Ádám Kincses's death mystery (1925), Second and Third Symphonies (1930,1933), and Three ironic portraits (1925) were all performed; the Opera House put on his fairy play, The three miracles of Józsí Árva (1930), and his comic opera, The two cavaliers (1934). The critics at first received his works with great enthusiasm, regarding him as the new star of progressive Hungarian music, in the tradition of Bartók and Kodály. However, his compositions - which combined the world of the musical modernisers of the turn of the century with the expressionism of the twenties, following neither Bartók nor Kodály - caused disappointment. It was partly as a consequence of this that Kósa found himself on the periphery of musical life. A part was also played in this, however, by the increasing shift of political life to the right. Kósa, who had Jewish origins, got fewer and fewer opportunities to appear in public: his biblical chamber oratorios (Joseph, 1939; Elias, 1940; Christ, 1943) could only be performed in tiny halls. Because of the laws relating to Jews, in 1942 he lost his job at the Music Academy, and in 1944, as a member of a labour brigade, found himself at Fertőrákos.

When he returned home at the beginning of 1945, he learned that his wife and daughter had been killed. From the second half of the 1944/45 academic year he was teaching again at the Music Academy. He immediately became a member of the Free Union of Hungarian Musicians, and in 1949 of the newly formed Association of Hungarian Musicians. From 1952 he became, as accompanist, a soloist of the National Philharmonic. In the 1949/50 concert season, a series of fourteen concerts commemorated the 200th anniversary of Bach's death: he played all the Bach pieces composed for keyboard instruments. In 1955, on the 270th anniversary of Bach's birth, he saluted the memory of the baroque master with a series of six recitals. However, the political spirit of the fifties did not favour the liberal-thinking composer: his opera, Tartuffe, was taken off the programme of Hungarian Radio, and his works on religious subjects could only be composed for his desk drawer.

It was finally the political consolidation of the sixties that made it possible for Kósa to find his place in Hungarian musical life. As the first sign of this, already in 1955 he received the Erkel Prize; in 1963 he was given the title, Meritorious Artist, and in 1972 that of Outstanding Artist. Between 1955 and 1966 he had six composer's evenings and several of his large-scale works, the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Symphonies (1957,1959,1969), the Villon oratorio (1961), and the Cantata humana (1967), written to the poems of Janus Pannonius, were given public performances. His first great successes as a composer, however, came only in the seventies, with his compositions on the theme of death: the Death Fugue (Paul Celan, 1967), Lament for a bull (Gábor Devecseri, 1975), I call you, swan (László Nagy, 1978), and the song cycle, In twilight (Anna Hajnal, 1977). It was with these works that the aged composer became one of the cultic figures of the Hungarian avant garde which developed in the sixties and seventies.

A. D.