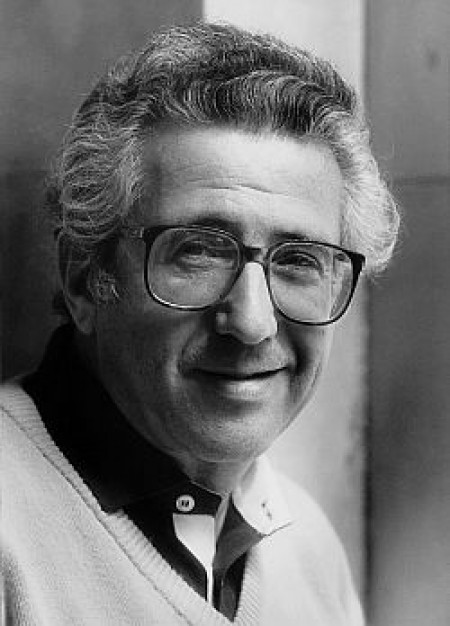

2 October 1935, Budapest

I began playing the piano at the age of five. Music-making was natural for me as my parents also studied at the Academy of Music though did not become artists, and we had two pianos at home. I started to play and make music, learned one year privately and I was admitted to the special school for exceptional young talents of the Academy. I continued my studies at the Academy of Music after the end of the war. Fortunately I was not a child prodigy so I took the steps of the career ladder fairly meticulously.'

Frankl was a student of Margit Gaál between 1941 and 1945. He studied in the classes of Ernő Szegedi between 1945 and 1950 and then of Lajos Hernádi until 1956. ‘I achieved my first significant success while still studying at the Academy, in Bucharest at the WFDY in 1953, where I was awarded 3rd prize at an international competition. From then on I was talked about, attention turned to me and took part in more and more contests.' He was winner of the Marguerite Long competition in 1957, two years later he won first prize again at an international competition in Rio de Janeiro (an honorary citizen of which he has been since 1960). He was winner of the Sonata Competition in Munich in 1957 with György Pauk. He lived in Paris between 1958 and 1961. In 1962 he moved to London and gave his first recital in England in the Wigmore Hall. He has been still one of the most engaged pianists of the English musical life since then. He played the Piano Concerto of Benjamin Britten at the Edinburgh Festival under the baton of the composer in 1968. He debuted in the United States the same year. ‘György Széll had a significant impact on my career for whom I played first overseas. I played works of different styles for him, and he did not say a word during almost the entire performance. Finally he turned back at the door and told me he introduces me in New York, I was to play Mozart with him and the Cleveland Symphony orchestra.' He worked with the most excellent American orchestras (Boston, Chicago and Philadelphia) and conductors (Abbado, Boulez, Doráti, Kertész, Maazel, Masur, Muti and Sanderling).

He has been a frequent guest in Hungary since 1972. ‘I will never forget my recital at the Academy of Music I gave after a fourteen years-long pause in 1972. I felt I took the plunge to the deep end then. All my former teachers were there, familiar faces appeared in the audience, lots of my onetime class-mates, colleagues, and friends came to hear me. The stage was also full of audience, too. I was sitting there motionless for minutes and had to focus very strongly so that I could start to play. That silence, that expectation has still remained a memorable one for me.'

He has been a professor of Yale University in the past decade. ‘I had a feeling that music-making has been developing in the wrong direction. In my opinion the point is the individual tone and natural music making. That whatever piece can be heard one should know after the first some measures the composer and performer of the work. I prefer the trend that is represented by Annie Fischer, Tamás Vásáry or András Schiff, and that kind of music playing is dying out. Many people play music in a uniformed way these days. I thought it must be something to do besides complaining. Therefore I accepted the invitation from Yale University.'

He plays chamber music concerts regularly with György Pauk and Ralph Kirshbaum. ‘We play together with György Pauk since childhood. Our acquaintance and friendship began at a football field and continued then at the Academy of Music and later in London.'

His orchestral repertoire involves all the piano concertos of Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Liszt and Bartók. He recorded all the piano works of Debussy and Schumann.

György Kroó reported the following after one of his recitals in 1997: ‘Peter Frankl played Schumann's Piano Concerto in a magnificent interpretation that evoked the spirit of Annie Fischer worthily. It is just amazing that Frankl can display as a chamber musician at the stranding of a concerto and at any point of its form. The way he translates the initiatives of the orchestra, the characters at all, or even the main theme ex. at the recapitulation to the private language of the piano is also special. By the alternation of the private sphere and the publicity of the stage his performance lighted sharply into the spirit of the work. [...] Frankl evoked the character most reminding to the interpretation of Annie Fischer in the recital with his suggestive piano playing in the last movement: the student-like devotion, enthusiasm, the openness of the music, the gesture of head-raising, an impetus of not the legs but the spirit.'

M. Sz.