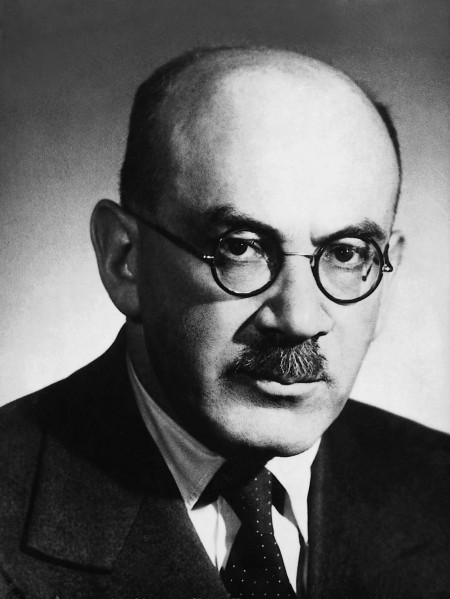

2 August 1899, Budapest - 21 January 1973, Budapest

‘Kodály was the strictest educator, the most demanding and the most inspiring. Every time I left him I felt that I took the atmosphere of the mountains. …he was also full of German, Italian, French and English culture, with Goethe, Dante, Verlaine and Shakespeare, with Latin, Greek and the Bible. And with so much music! The entire history, past and present of music was billowing in him – it was really unimaginable when he could absorb all these.' – wrote Bence Szabolcsi on his beloved professor, the great ideal, Zoltán Kodály, but he could have been characterized with the same words by his students later.

The name and work of Bence Szabolcsi connect organically to the establishment of Hungarian musicology and its growing of international demand. He studied law, history of literature and philosophy between 1917 and 1920 at the Hungarian University of Sciences in Budapest, and parallel to that he studied composition between 1917 and 1921 at the Academy of Music with Zoltán Kodály, Albert Siklós and Leo Weiner. György Kroó highlighted the decisive impact that Kodály had on the development of Bence Szabolcsi as a scientist: ‘Kodály meant first of all the absolute educational authority, classical literacy, the exceptional proficiency in European, mainly German and French literature, encyclopedic awareness and infallibility for him. As a prospective musicologist he was amazed by his knowledge in music history incomparable to anyone else's in Hungary, and recognition of the close connection of music history and ethnomusicology present in Kodály's consciousness was especially decisive for him. The ideal image of the musicologist was formed in Szabolcsi by the personality-model of Kodály.'

From 1921 Bence Szabolcsi studied history and art history with Wilhelm Pinder, music theory with Siegfried Karg-Elert and music history with Hermann Albert and Friedrich Blume at the University of Leipzig following his studies at the Academy of Music, from where he returned home with a PhD in Liberal Arts (musicology) in 1923. In that year he possessed the only musicology degree in Hungary. He wrote his first biography, on Mozart, during his Leipzig years and the topic of his dissertation was connected to the history of the Italian monody. Upon returning home he worked as a music critic, editor (of the journal Zenei Szemle) and publishing lector, and parallel to his studies in musicology his works in literal history were also published. In the years of the 1920s, and 1930s he was searching for old Hungarian memories of music history from the Middle Ages to the nineteenth century and as a result of that the first summary was created with the title A magyar zenetörténet kézikönyve (A Handbook of Hungarian Music History); still considered as basic literature today on the history of Hungarian music history. Another major, abiding project of him in these years was the Zenei Lexikon (Music Lexicon) edited together with Aladár Tóth, for which he also wrote hundreds of articles.

He was respected not only in Hungary – in 1933 he was awarded the Baumgarten-Award and he received the Kossuth Prize twice in his life. He was an internationally renowned scientist: he was elected member of the Royal Asiatic Society in London in 1936 and the International Musicological Society in 1938. From 1945 on he belonged to the Academy of Music as a professor already: he taught history of musical style and history of Hungarian music. He initiated and encouraged the establishment of the musicology department in 1951 that became the first institution of the education of musicologists in Hungary. He had a leading role as the Head of the Musicology Department in educating new generations of musicologists. György Kroó, János Kárpáti, Ferenc Bónis, István Kecskeméti, László Somfai, Marianne Pándi, János Kovács, Margit Tóth were among his first musicology students.

Radio series – for example Szabolcsi Bence tanít (Bence Szabolcsi Teaching) – preserved mosaics from the magic of the courses of Bence Szabolcsi for the young generation. He was corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences from 1948, and became a full member in 1955 as well as an editor of musicological periodicals (Magyar Zene, Studia Musicologica). In 1961 he established and directed the Bartók Archives of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences until 1973 as well as the Institute of Musicology of that from 1969. He was awarded the Herder-Award two years before his death. His former students who could still know him personally profess on his pedagogic and human greatness: ‘Nobody was so much a musician like him among our music historians. He was not only a trained composer and outstanding pianist, but he carried the history of music in his fingers all times. Those juvenile fingers still played in a virtuosic way when he became from the former analytic student to a professor who amazed his students with his knowledge in improvisation any time.' – recalled István Kecskeméti.

His human lineaments were brought closer to us by József Ujfalussy: ‘He accepted his students with his inspiring words, encouraging look immediately as his colleagues, irresistibly attracting them as companions to exciting joint spiritual adventures, from the music folklore of Asia to the hall of music, arts, literature and philosophy of Europe, to wonderful travels from melodies hardly known in Hungarian music history to the art of Bartók and Stravinsky. Therefore we, his colleagues made ourselves his students constantly, again and again relying on him amazed and followed him to the realm of his infinite treasures. His student-like, conspiratorial smile brightened up then and made benevolently unobservable the endless distance between the degrees of our knowledge. The superiority of his spirit was not stunning but he lifted us raising us to himself in the original, dictionary's meaning of the word.'

D. Zs.